Separation

Ever wonder why people of different racial backgrounds live in separate communities in the U.S.? Or why do most of our close friends share our race or ethnicity?

We might think it’s all personal choice. However, racial separation was part of the American design, with colonization and enslavement setting the stage for centuries to come. The devastating effects of our separation continue today, with many communities of color cut off from access to essentials like jobs, transportation, safe housing, healthcare and good food.

The legacy of racism in the United States is multifaceted. It touches every community across all backgrounds and cultures, albeit in unique ways. The history presented here is by no means exhaustive, rather it represents several turning points that created the present realities faced by all people living in the U.S. today.

COLONIZATION

Treaties (1600-1787)

Colonization and the treatment of Indigenous people were all about who controlled the 3.7 million square miles that became the United States. Every Indigenous group we refer to as a tribe, was and still is, a sovereign nation. Native Nations entered into treaties with European governments as the Spanish, French, and British explored and took over land. When the U.S. became an independent nation, it also entered into treaties with Native Nations. Any place a person lives in the U.S., a treaty likely covers that person’s right to live there. (Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. An Indigenous People’s History of the United States; Learn more at NPR.)

Removal & Reservations (1828-1887)

Native Americans were removed from their land and forced to migrate westward. Treaties with Native tribes led to land loss and the creation of reservations, commonly on land that was more difficult to cultivate. The reservation system ultimately confined Native Americans to these areas and limited their mobility, access to resources and independence (education.nationalgeographic.org).

Allotment & Assimilation (1819-1969)

The federal government forced removal of Native people from their ancestral lands and children from their homes and communities.The Indian Civilization Act of 1819 eradicated Native family structures, economies and claims to ancestral lands. Between 1819 to 1969, the U.S. operated and supported 408 Federal Indian Boarding Schools across 37 states and territories. During the Indian Reorganization era (1928-1945), an act granted more autonomous control over land to Native Americans if they adopted western-style governance structures. (Learn more from the Department of the Interior.)

Termination & Relocation (1945-1968)

New policies ended support and protections for Native American Nations and offered money to individuals who agreed to relocate to selected urban areas, find work and integrate into these communities, which were commonly under-resourced.

Supreme Court Reduces Native Sovereignty (2022)

The Supreme Court overturned legal precedent that protected the rights of Native Nations to exercise sovereignty on their lands. The court’s decision in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta allows state courts to prosecute criminal cases on tribal land, which were earlier handled by tribal courts. This implies that reservations are part of U.S. states rather than sovereign nations.

SEGREGATION

Enslavement (1619-1863)

Slavery existed in all 13 colonies, North and South. Wealthy plantation and business owners separated people by race to maintain control over their labor force. During the late 1700s, most Northern lawmakers abolished slavery in state constitutions, however racial segregation was still ingrained across these communities. In the South, White and Black people lived in close proximity. Cross-racial relationships were characterized by violence and deprivation of rights perpetuated by White enslavers and overseers toward Black people during this era (Winthrop B. Jordan. White Over Black: American Attitudes toward the Negro, 1550-1812. Michelle Alexander. The New Jim Crow).

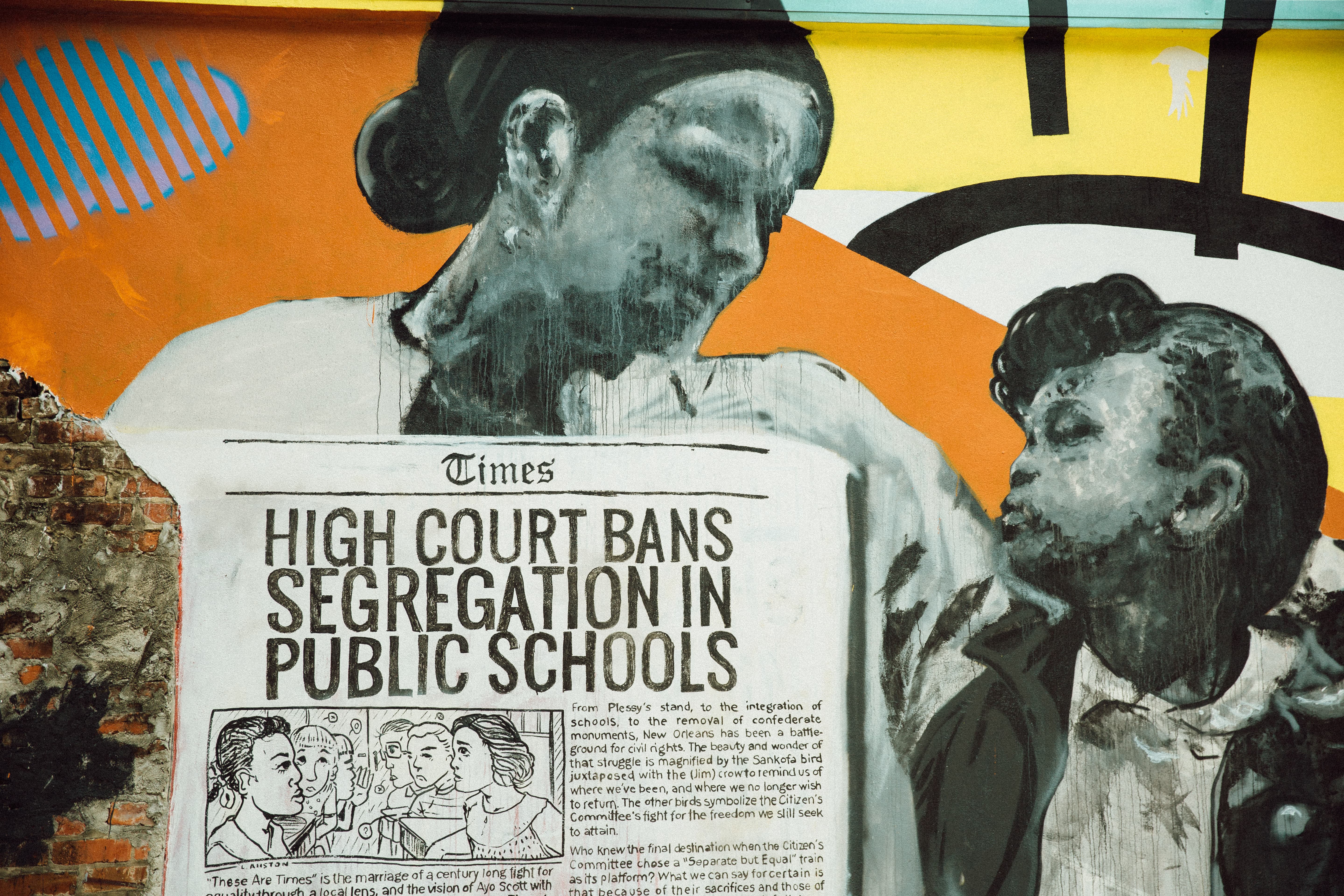

Jim Crow (1890-1954)

Following slavery, an 11-year Reconstruction period led to major political gains for newly freed Black people, making a multi-racial democracy more possible. Jim Crow arose against these strides by exploiting many people’s belief in Black people’s inferiority. Southern plantation owners wanted to maintain racial hierarchy and control over the labor force and thus baked separation into state and local laws. By 1900, every Southern state established Jim Crow laws to keep Black and White people separated in every facet of life, including: schools, churches, neighborhoods, recreation, hotels, hospitals and even cemeteries (Michelle Alexander. The New Jim Crow).

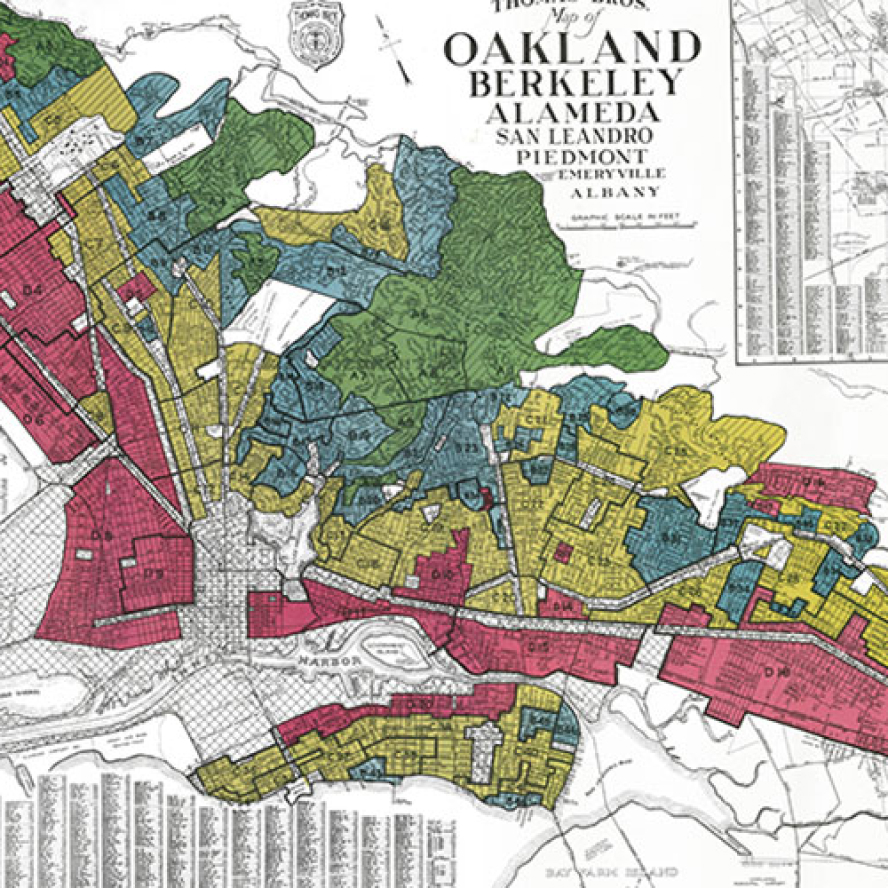

Redlining (1934-1968)

Practically speaking, a form of Jim Crow existed in the North, as well. In 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the National Housing Act, creating the Federal Housing Administration, which sanctioned the practice of redlining almost immediately. Redlining denied or limited financial services, like loans, mortgages and insurance, to Black neighborhoods and communities. This ensured White and Black neighborhoods remained separate and limited people of color’s ability to build wealth through property ownership (nytimes.com, federalreservehistory.org and npr.org).

White flight (1950s -1980s)

This phenomenon gained momentum in response to the desegregation of schools and neighborhoods. White people moved out of more racially integrated urban areas into rural and suburban areas, creating more racial and ethnic separation within cities across the U.S. and drawing much-needed tax revenue away from urban centers.

Gentrification (1990s-today)

A process seen across the U.S., wealthier individuals and families, oftentimes White people, move into lower-income urban neighborhoods bringing new businesses and wealth into the community. This shifts the racial and ethnic composition and the economics in the area, leads to a rapid increase in housing prices and property taxes, drives lower and middle-income individuals and families out and displaces the people (often people of color) who lived there before.

RACIAL

HEALING

TODAY

We can’t heal or create greater racial equity if we don’t know each other. Racial healing involves building trusting relationships that help us work together to address the impact and damage caused by racism. Changing the systems that separate us starts with challenging our individual impulses to separate. On this National Day of Racial Healing – and year round – find a way to build common ground with people who share your city, town or organization.

Explore Inspiring Stories of Racial Healing

- In Charlotte, North Carolina, a coffeehouse chat made talking about race easier during National Day of Racial Healing 2022.

- In the Keeweenaw Bay Indian Community in Michigan, early childhood educators focus on healing from the legacy of boarding schools by bringing Indigenous language and culture into classrooms.

- In Battle Creek, Michigan, a community dinner created connections across race and culture during National Day of Racial Healing 2022.

- In Richmond, Virginia community gardeners learned local history about separation and redlining while cultivating new greenspaces on vacant lots.

- In suburban Minneapolis, Minnesota, the Just Deeds Project helps homeowners remove restrictive covenants placed on their property titles during the redlining era, so a person of any racial background may purchase homes in the future.

Take Action Today

4 Ways to Create Connections on the National Day of Racial Healing:

- Host a small relationship-building lunch, dinner or coffee chat for neighbors and friends using our Conversation Guide.

- Find a cultural performance or exhibit featuring artists from a racial background/s other than your own. Bring the whole family!

- Visit a local history museum to learn more about your community’s origins. Take the opportunity to tour museums that focus on the experiences of communities of color in your city or state.

- Homeowners: Make housing more accessible to people of color in your area. How? Check your property titles for restrictive racial covenants placed by previous owners. Then, research the local legal process for removing them.